Learning to Erupt

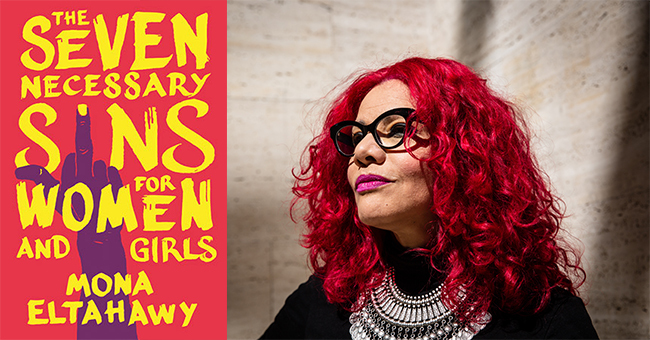

As we approach March—a month dedicated to both celebrating women's history and observing International Women's Day—I find myself sitting with a book that refuses to let the reader sit comfortably; The Seven Necessary Sins for Women and Girls by Mona Eltahawy. The title itself is a deliberate provocation, a direct challenge to the Christian framework of the seven deadly sins that has so deeply shaped Western morality. Where the church traditionally named pride, greed, wrath, envy, lust, gluttony, and sloth as the vices that lead us away from righteousness, Eltahawy reimagines the list entirely. She offers a fierce, polemical text built on the premise of seven necessary, foundational "sins" of anger, attention, profanity, ambition, power, violence, and lust. She argues that for women and girls, these are not vices to be suppressed but virtues to be cultivated. They are, in her view, the very tools necessary for liberation.

Here I focus on the first of those sins: Anger.

We are called by our 8th Principle to engage in "individual and communal action that accountably dismantles racism and other structural barriers to full inclusion," so we must examine our own relationship with this emotion. As Canadians in a polite, educated, and largely liberal white church community, anger is often seen as un-spiritual, unproductive, or simply impolite. But Eltahawy asks us to reconsider: What if anger is not the problem? What if anger is the cure?

The Pilot Light of Justice

Eltahawy argues that anger is not destructive; it is foundational. Like a pilot light waiting to ignite something larger, anger is "that bridge that carries feminism from idea to being, from the thought 'How the fuck is this happening?' to 'This must fucking stop'" (p 21).

But girls are socialized to extinguish this flame. From an early age, they learn to turn their rage inward. Patriarchy prefers "sadness and shame" over outward anger because "sadness does not terrify patriarchy" (p 30). When we teach girls to be "nice," we aren't protecting them—we are snuffing out their pilot light and ensuring the system faces no threat.

She points out the hypocrisy: when she urges nurturing anger in girls—keeping that pilot light burning—"people—mostly men—worry that you are encouraging violence" (p 30). This defends a monopoly on who gets to burn hot. "It is almost as if they think that boys have a copyright to anger... 'Let boys be invincible. Teach girls to be invisible'" (p 29). Even in anti-establishment spaces like the punk music scene, men rarely challenge patriarchy because they benefit from it (p 32). They guard the flame while telling girls their spark is dangerous.

Anger as Freedom

For those who have been historically silenced, anger is not a loss of control; it is the regaining of one's self. Eltahawy quotes Owethu Makhatini, a Black woman who writes in her essay A Lot to Be Mad About: Advocating for the Legitimacy of a Black Woman’s Anger:

"I fought long and hard not to be the angry Black woman, and yet here I am. I am livid. I have denied my anger. I have been ashamed of my anger... I am angry because I care. I am angry because I want to be and feel free. I care about how the world invested in breaking my people and me. I want to fuck it all up. Set everything on fire and start over" (p 23).

This is the prophetic rage that the world needs. It is the rage of Kyle Stephens, who looked at her abuser, former USA Gymnastics and Michigan State University doctor Larry Nassar and declared, "Little girls don’t stay little forever... They grow into strong women that return to destroy your world" (p 25). It is the eruption Ursula K. Le Guin described to young graduates of the women’s college Bryn Mawr in 1986: "We are volcanoes. When we women offer our experience as our truth, the human truth, all the maps change. There are new mountains" (p 26).

A Hard Look at Ourselves

Here at home, in Canada, we often pride ourselves on being "better" than the toxic cultures we see south of our own border. But Eltahawy warns against this delusion, specifically calling out white women who succumb to denial about realities for women that are right in front of them. They push the problem away, pretend it is something that can only happen elsewhere in bad places far away.

The truth is that the same dynamics exist in our neighbourhoods, our schools, and yes, our churches. We see it when we deny life-preserving healthcare to trans youth. We see it when we allow a government to strip the rights of teachers—a profession made up of a majority of women—forcing them into dangerous contracts. We turn away from these realities because we want to believe we are not like "them." But as Eltahawy notes, this denial is a privilege of the sheltered.

She writes of white American women who finally became angry after Trump was elected, asking, "Where have they been?" Their rage was treated as a revolution, when in reality "they are finally catching up to the revolution of rage that swept up the rest of us" (p 34). For those of us who benefit from white privilege in Canada, this is a humbling call to listen. The anger of Black women, Indigenous women, and women of colour is not new. It has been burning for centuries. We are merely late to the fire.

A Curriculum for Our Congregation

Eltahawy proposes a new curriculum for the world—one designed to teach girls freedom rather than compliance. At its heart is a radical commitment to nurturing their rage. She writes, "I want to bottle-feed rage to every baby girl so that it fortifies her bones and muscles. I want her to flex and feel the power growing inside her" (p 26).

What would it look like for us, as a faith community, to deliver such a curriculum? It would mean creating space for women and girls to be fully themselves—not just the pleasant parts, but the furious parts, too. It would mean, as Eltahawy insists, teaching boys "that girls do not owe them time, attention, affection, or more; that the bodies of girls belong to girls" (p 21).

And it would mean embracing a faith that is not shackled to "respectability." As Eltahawy warns, "A feminism that must respect 'culture' and 'religion' is a feminism that is shackled to respecting two basic pillars of patriarchy." We need a faith that is "robust, aggressive, and unapologetic; a feminism that defies, disobeys, and disrupts" (p 21).

Closing

"For too long, men have called us names designed to insult... Feminazi. Ball-breaker. Crazy feminist, Bitch. Witch. Yes, I am those things, we must say. Yes, I am an angry woman. And angry women are free women" (p 35).

As we move through Women's History Month, may we stop asking angry women to calm down. May we stop instructing girls to be nice. Instead, may we get out of their way as they learn to erupt.

After all, as Le Guin promised: when we erupt, the maps change.